The Scope of Comparison Prior Art in Design Patent Infringement

by Dennis Crouch

The pending appeal in Columbia Sportswear North America, Inc. v. Seirus Innovative Accessories, Inc., 2021-2299 (Fed. Cir. 2022) raises a number of important design patent law questions, including an issue of first-impression of the scope of “comparison prior art” available for the ordinary observer infringement analysis under Egyptian Goddess, Inc. v. Swisa, Inc., 543 F.3d 665 (Fed. Cir. 2008) (en banc) and its key predecessor Smith v. Whitman Saddle Co, 148 U.S. 674 (1893). Since Egyptian Goddess, the Federal Circuit has placed renewed importance on the claimed “article of manufacture,” but not in the comparison portion of infringement analysis.

In 2021, the Federal Circuit issued the important, albeit short-winded, design patent decision In re SurgiSil, L.L.P., 14 F.4th 1380 (Fed. Cir. 2021). In SurgiSil, the court held that the particular article-of-manufacture recited by the claims should not be ignored, even for anticipation purposes. SurgiSil’s cosmetic lip implant has a remarkably similar shape to lots of other two-pointed cylinders. As an example, the image above shows the SurgiSil lip implant (bottom) compared against a prior art blending stump (top) sold by Blick.

The PTAB found SurgiSil’s claim anticipated, but the Federal Circuit reversed–holding that a blending stump does not anticipate a lip implant.

Utility patent attorneys are familiar with the Schreiber decision that allows for non-analogous art to be used for anticipation rejections. In re Schreiber, 128 F.3d 1473 (Fed. Cir. 1997)(“whether a reference is analogous art is irrelevant to whether that reference anticipates”). In some ways, Schreiber could be seen as intension with SurgiSil. In reality though the two decisions fit well together and SurgiSil did not make a special design patent rule or reject Schreiber. Rather, Surgisil simply interpreted the claim at issue as requiring a lip implant and then found that a non-lip-implant didn’t satisfy that claim limitation. I will note that SurgiSil was a patent applicant’s appeal from the USPTO. The case was remanded back to the USPTO 10 months ago, and not patent has issued yet. I expect that the examiner has now rejected the claim on obviousness grounds.

SurgiSil, coupled with the court’s prior decision in Curver Luxembourg, SARL v. Home Expressions Inc., 938 F.3d 1334 (Fed. Cir. 2019), place new weight on the claimed ‘article of manufacture.’ On open question is how this focus should play out in the infringement analysis under Egyptian Goddess, Inc. v. Swisa, Inc., 543 F.3d 665 (Fed. Cir. 2008) (en banc).

A design patent’s scope is typically determined by its recited article of manufacture and single embodiment shown in the drawings. An accused design does not have to exactly match the drawings. Rather, what we do is ask whether an “ordinary observer” would be deceived that the accused design is the patented design. Egyptian Goddess. Before making the comparison, the ordinary observer is supposed to become familiar with the prior art (if the issue is raised). The prior art is used to help measure the scope of the claims. If there is no prior art remotely similar, then the patented design is going to be given a broader scope by the ordinary observer; on the other hand, when the prior art is quite similar to the patented design the patent scope will be narrow. Of note, comparison prior art is only used at the accused infringer’s behest, and so the issue will strategically arise only when the defendant has evidence of very similar prior art.

The open question: What prior art should we look to when making a comparison? That question is before the court in Columbia Sportswear North America, Inc. v. Seirus Innovative Accessories, Inc., 2021-2299 (Fed. Cir. 2022) (pending before the Federal Circuit). In the case, the accused infringer (Seirus) had some spot-on comparison prior art, the only problem is that the references were sourced from disparate articles of manufacture far afield from Columbia’s claimed “heat reflective material.” The case is potentially big because of the profit disgorgement remedy available in design patent cases. 35 U.S.C. 289 (“[the infringer] shall be liable to the [patent] owner to the extent of [the infringer’s] total profit”). And, we might expect a strong potential that a decision here on the infringement side will reflect-back to also apply in any obviousness analysis.

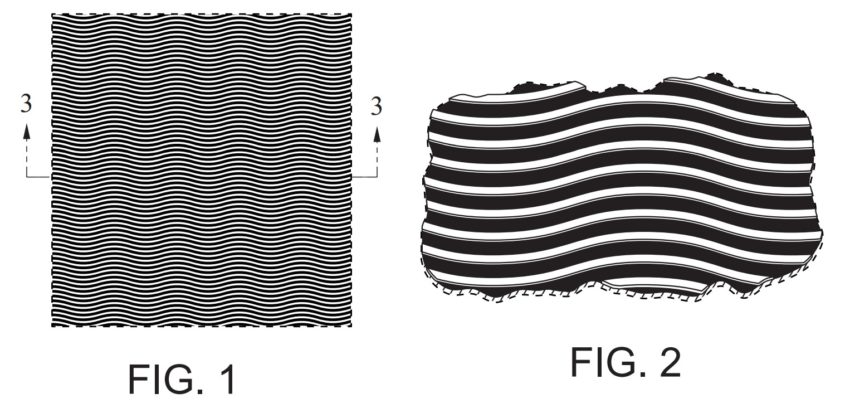

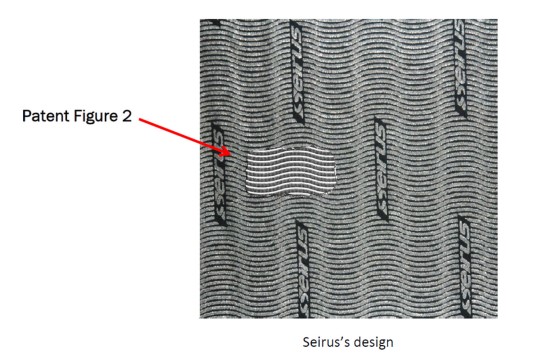

I have written before about the Columbia v. Seirus lawsuit that involves the reflective (but water permeable) inner layer that both use to line their cold weather gear. Columbia’s Design Patent No. D657,093 claims the “ornamental design of a heat reflective material” as shown the drawings. As you can see from Figures 1 and 2 below, the design shows a wave-like design, which the inventor (Zach Snyder) says was inspired from his time living in Arizona and seeing heat ripple mirages rising from the ground.

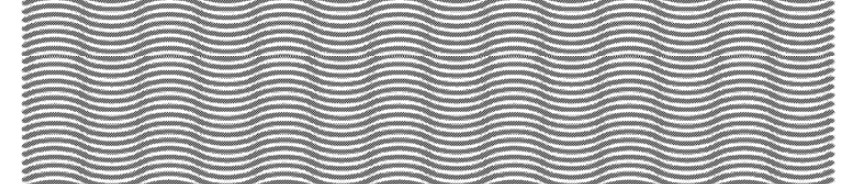

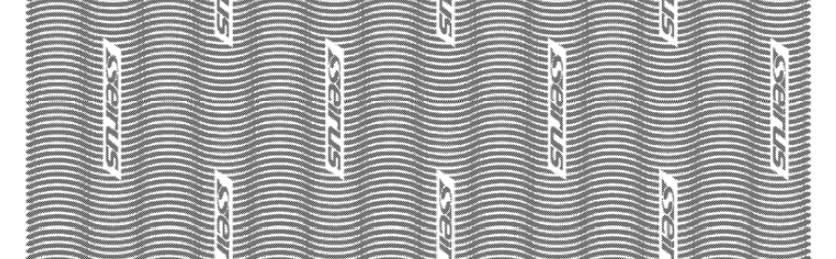

The Seirus product is similar and uses a wave/ripple design. Early Seirus products lacked branding, but Seirus later added its brand name to the designs in order to promote its brand and avoid confusion. If you have seen these designs on apparel liners, it is coming from Seirus brand. Although Columbia has the patent, the company initially launched its product using a pixilated design (covered by a separate design patent) and later decided to not adopt the wave in order to avoid confusion with Seirus.

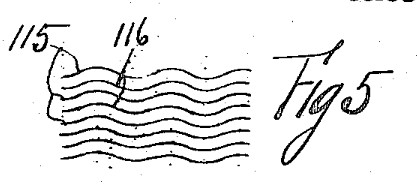

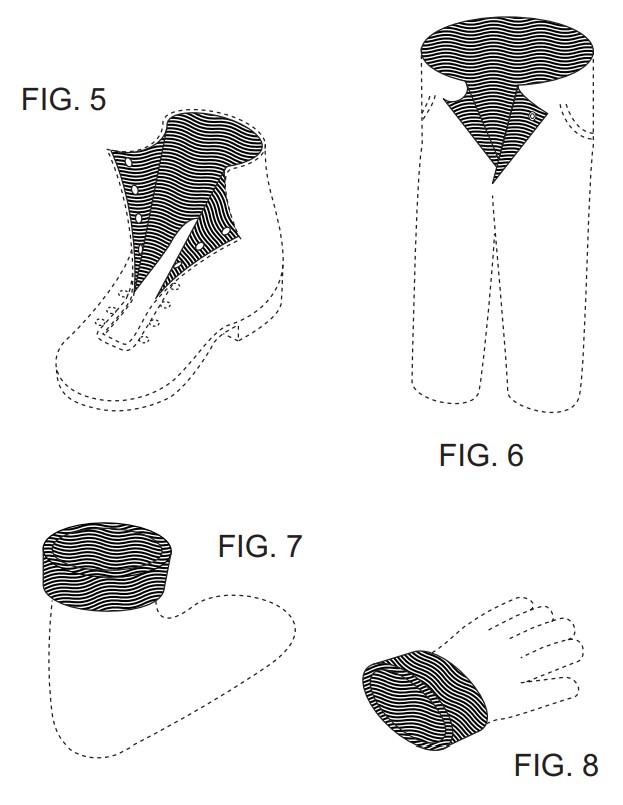

At trial, the jury was shown images of the patent as well as the accused product in order for it to conduct the ordinary observer test. The Egyptian Goddess infringement analysis also requires consideration of the prior art. Seirus presented some visually close references, including a 1913 utility patent covering the inner tire liner. (Fig 5 below from US1,515,792). The court limited the scope of comparison prior art to only fabrics for the Egyptian Goddess comparison. That tire patent was allowed because the inner layer was in a fabric form.

At trial, the jury sided with the defendant Seirus and found the patent not infringed.

Now on appeal, the patentee argues that infringement analysis prior art (“comparison prior art”) should be limited by the patent’s stated article of manufacture. If the Columbia court had limited comparison prior art to only those showing “heat reflective material,” it would have all been excluded. But, the district court allowed-in the prior art from unrelated arts, and then went further by precluding Columbia from asking the jury to reject the unrelated comparison prior art. The basic idea for limiting comparison prior art stems from the same notions expressed by the Federal Circuit in SurgiSil and Curver Luxembourg: design patents do not cover bare designs but rather designs “for an article of manufacture.” 35 U.S.C. 171. And, that “article of manufacture” portion of the law should remain at the forefront of all design patent doctrines. In Egyptian Goddess, the patent covered the “ornamental design for a nail buffer” and all the comparison prior art references were also nail buffers. 543 F.3d 665 (Fed. Cir. 2008). Likewise, in Whitman Saddle, the design patent at issue was directed to a “design for a riding saddle,” and the prior art used in comparison was also a riding saddle. 148 U.S. 674 (1893). But, the district court in Columbia refused to limit comparison prior art to only the same article of manufacture. The district court concluded that such a ruling would improperly import too much functional into the design patent right — design patents cover form, not functionality.

In my view, Columbia’s proposal of a strict article-of-manufacture limitation is too limiting because it does not reflect the perspective of either a designer or an ordinary observer and because it offers the potential opportunity for undue gamesmanship in the writing of the claims. As an alternative rule of law, the patentee suggests that the scope of comparison prior art be limited to articles that are either the same article of manufacture or “articles sufficiently similar that a person of ordinary skill would look to such articles for their designs” This test comes from Hupp v. Siroflex of Am., Inc., 122 F.3d 1456 (Fed. Cir. 1997) and was used to define the scope of prior art for an obviousness test rather than comparison prior art for the infringement analysis. But, it seems to roughly make sense that the same scope of prior art should be considered both for obviousness and for infringement analysis — although obviousness is from the perspective of a skilled designer and infringement is looks to the ordinary observer (i.e., consumer).

I would argue that even Columbia’s broader alternative approach is too narrow. In Columbia’s asserted patent, the images (below) show the use of the material as an inner liner for various articles of clothing as well as an outer liner for a sleeping bag. It would make sense to me that an ordinary observer might be deceived by other apparel liners using the same wave, even if not “heat reflective;” and thus that a jury should be permitted to consider those products as comparison prior art in the Egyptian Goddess infringement analysis. Unfortunately for Columbia, my broader notion of comparison prior art makes their case difficult since at least one of the comparison references shown to the jury was the wave pattern used as the outer liner of a rain jacket, US5626949, and all of the references are some form of fabric. Further, in some ways Columbia opened the door to a very broad scope of comparison prior art by including Figure 1 (shown above) claiming the material as a pattern apart from any particular application (such as those shown in other figures).

There are two primary procedural mechanisms to limit the scope of comparison prior art. (1) exclude prior art from consideration as irrelevant; (2) allow the jury to consider the evidence, but allow the parties to also introduce evidence regarding the extent that the prior art might influence the ordinary observer or skilled artisan. These are all issues that folks have repeatedly worked through (and continue to argue about) with regard to validity and obviousness in utility patents, but they remain undecided in the design patent infringement context post Egyptian Goddess. The appellate brief asks three particular questions on point:

- What is the relevant scope of “comparison prior art” that is to be considered in a design patent infringement analysis?

- Is it error to instruct the jury that all prior patents are comparison prior art to a design patent, and to fail to instruct the jury to limit the scope of comparison prior art to those related to the claimed article of manufacture?

- Was it an error to prohibit Columbia from distinguishing comparison prior art on grounds that it failed to disclose a the claimed article of manufacture?

Columbia Sportswear North America, Inc. v. Seirus Innovative Accessories, Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2022) (Appellant’s opening brief).

Now lets talk about the Logo. The figure above might be the key exhibit of the whole case. The figure shows the Seirus design with an overlay from Figure 2 of the Columbia patent. As you can see, the waves fit up almost perfectly (after a bit of resizing). A detailed analysis can find other differences in the waves, but the key visual difference is the repeated Seirus logo.

The importance of those logos was a key element of the prior appeal in the case. Columbia Sportswear N.A., Inc. v. Seirus Innovative Accessories, Inc., 942 F.3d 1119 (Fed. Cir. 2019) (Columbia I) The leading precedent of L.A. Gear, Inc. v. Thom McAn Shoe Co., 988 F.2d 1117, 1124 (Fed. Cir. 1993) indicates a copycat cannot escape design patent infringement by labelling products with a different trade name. (Images of the L.A. Gear patent and Accused infringer below). In Columbia I, the Federal Circuit distinguished L.A. Gear by explaining that the precedent “does not prohibit the fact finder from considering an ornamental logo, its placement, and its appearance as one among other potential differences between a patented design and an accused one.” Id. Rather the logo should be considered for its “effect of the whole design.” Id. (Quoting Gorham).

In the second trial, Seirus spent some time focusing on the logos as important design elements and that may well have made the difference for the jury. In particular Seirus provided evidence that the logos were arranged and designed in a decorative way to be both ornamental and to catch attention. In addition, the logos are used to break-up the wave so that folks don’t get hypnotized. In other words, the logos were more than mere labeling. Still, on appeal Columbia has asked the appellate court to address these issues once again in the form of objections to the jury instructions:

- Did the court err by failing to instruct the jury – that in this case – confusion (or lack of confusion) as to the source of goods “is irrelevant to determining whether a patent is infringed?” Columbia suggests that the problem comes about with the infringement instructions that focus on “deceiving” consumers. Columbia also implies that in some cases customer confusion as to source could be relevant evidence — such as in cases where the patentee also manufactures a product covered by the patent. Here, however, Columbia does not practice the patented invention.

- Did the court err by failing to instruct the jury that “Labelling a product with source identification or branding does not avoid infringement?” (Quoting L.A. Gear). This final question appears to be rehashing the issue decided in Columbia I and so has presumably become unappealable law of the case. For its part, Columbia argues that “[t]o the extent Columbia I is in conflict with Unette, Braun, or L.A. Gear, the prior cases control.” On this point, it appears that Columbia may be preserving the issue for en banc or Supreme Court review.

Read the briefs: